Since leaving high school and my home in York, Pa, I have gradually amassed a shrine of sorts that travels everywhere with me. It consists of items from people and places that hold very important places in my heart, and will forever. Since my freshmen year of college it has grown considerably, but I am still able to look at each piece of it, and remember exactly where or who it is from, and why it is special.

First there is a toucan. This is a rubber toucan that I have had longer than almost anything in my current possession. Its toes have almost all fallen off, so it must lean against something to stand upright. Silas gave this figure to me after a family vacation to Florida or one of the Carolinas.

He has always known how to pick out small gifts that surprise me and show me how much he thinks of me. I remember one time he came to visit my house and saw the toucan on the floor, (since even then it was bad at standing upright, it fell often) and I felt I really let him down when he appeared to be hurt that it was laying on the floor. Since then, I have always felt bad if I see it laying on its side.

There is also a ubiquitous Buddha figure, which for a long time meant nothing to me aside from the memory of a trip I took to Williamsburg, Va, with Silas. We were wandering around a flea market, and I bought this small wooden statue of this Buddha just because it looked attractive to me. I had no clue what Buddhism was, or that it would come to be a majorly transformative force in my life some years later.

Behind the Buddha is a card of a monk that Sara gave me last year for my Bday. In dark times it pushes me into the next day.

The Buddha is sitting upon two river stones I took from Little Pine Creek, one of the places where I began to realize my serious love for the outdoors, my friends, and simple fun. My father first took me to the banks of where I found these stones, and taught me how to fly-fish. I caught one fish in three days. It was a beautiful rainbow. I had no clue what I was doing then. I didn't even know where my fly was when I felt the fish tug. A few years later, Silas and I went fishing there, and we decided to jump in the freezing creek since we hadn't showered in a few days. We screamed and flailed about, and after the stinging subsided, we swam in the crystal clear current, chased trout, and were free. While we warmed up in the sun on the bank, we began skipping stones. This river bank is still the best place I know for skipping stones. One of the funniest memories of my life is our attempts to skip these stones using our non-dominant arms. The awkwardness with which we failed to skip these rocks had us rolling around on the banks.

The small white stone upon the river stones is what I believe is an agate, or an oolid. This stone was sent to me from the shores of Lake Michigan by a dear friend whom I met in Washington, Sarah W. If I remember correctly, these are fossils of small, spherical organisms that became clumped together and fossilized. These stones get rolled around in the surf, becoming polished pebbles of visible fossils.

The piece of bark setting next to this small pebble is very special to me. This bark comes from the remaining cedars of Lebanon. Joelle, a very important friend from Germany sent it to me during one of her visits to her father in Lebanon. The Cedars of Ledanon are some of the oldest, tallest and most ancient and sacred trees in the world. The cedar forests of Lebanon are fabled in the bible, but are long gone due to the same human hunger that scars the Amazon Basin, and the slopes of the Pacific Northwest. This bark is from one of the few remaining sages.

In front of the piece of bark lay two buckeye chestnuts. Late one college night I was walking with some dear friends, Pat and Sarah, along one of the circuits of beautiful lewisburg that had slowly become very familiar to us. We intuitively followed each other aimlessly from street to street, to our favorite victorian houses, spots on the river, and our favorite trees. Each fall we kicked the buckeyes up the road and crunched them beneath our feet. I tasted their bitter tannins, and we talked about how they probably got their names from early taxidermy practices. We held the large chestnuts up to our eyes, imagining them painted like an eyeball and plugged into a trophy buck hanging on someone's living room wall. I kept a few in my pocket one night, so I could cling to those chilly nights when all was perfect.

Next to the Chestnuts is a plug of aspen branch, which I intended to carve into a keychain, but later found it fit perfectly on the shrine. I picked this up when Sara and I first truly met each other. I was visiting Co and the mountains for the first time, and we went on a short hike. This is where I found Sara, and saw the person I felt was hiding beneath the surface all the years we sang together at Bucknell.

Next, there is a white piece of driftwood setting atop a darker piece of driftbark. Both came from the Quilcene Bay, during the first summer I lived in Washington. I would ride my bike down Linger Longer Rd. each day after work, and plunge into the salty water, swim with a lone seal, or catch crabs, and some days I would sift through the driftwood, amazed at the designs nature could make with water, wood, and stone. These pieces will stay with me forever I hope. The dark piece of bark came from when I finally returned to Quilcene after being away for several years.

Then there is a sage smudge made by Sara. After I visited her that first summer in Co, and remarked over my love for Sage, she later sent me this after we had finally began dating. It hung in my car for awhile, and now travels from place to place with me.

Relics from the beginning of Love are so latent with nostalgia.

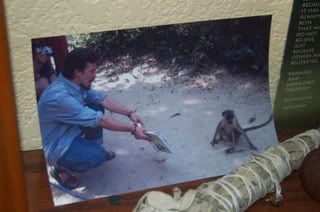

Behind the sage smudge is a picture of Peter, during his time in The Gambia, Africa. My time spent with Peter was so short-lived, yet his friendship was/is so uniquely touching and important in my life. I look forward with hope that we will live together again some day.

I wonder what will be next. There are a few places and friends who are not represented in this shrine, and while you are very important to me, it gives me hope that there are memories to come in places we have yet to be to add to this shrine.